What is the pinnacle of motorsport? It’s a thorny and passionate subject motorsport fans burst blood vessels debating over. For me, the simple fact that Formula 1 cars hold every lap record on any circuit they have raced on settles the argument once and for all. Sure, WRC is more spectacular, there’s more wheel-to-wheel racing in IndyCar racing and nothing comes close to the split-second photo finishes in Moto GP. An F1 race may seem boring in comparison, but for ultimate speed, the ability to shrink time on a given track, there’s nothing on the planet that beats an F1 car. And speed is what motorsport is all about, isn’t it? It’s the reason why F1 attracts, by far, the best drivers in the world and the cleverest engineers to build their cars. At this topmost echelon of the sport, everything happens on a stratospheric scale. It starts with eye-watering budgets that pay for top talent all around, which includes the development of racing cars built with NASA levels of technology. So it wouldn’t be an exaggeration to say that Formula 1 is the closest you’ll get to space without leaving Earth.

To first comprehend what that really means and then tell you what it’s really like to drive a genuine, full-blown Formula 1 car, I’m at the Paul Ricard circuit in the south of France waiting to be strapped into one. It was here that only two months earlier, Lewis Hamilton won the 2018 French Grand Prix and today, with the eerily empty grandstands in front of me (thank God!), I’m being given a chance to play F1 driver for an afternoon.

It was with a sense of déjà vu that I wiggled my distinctly non-F1 frame into the tight confines of the carbon-fibre tub and, with knees pinned together, stretched my legs into the narrow nose to probe the pedals. This was an environment I am very fortunate to have experienced twice before.

The first time was in 2001 when I drove an old but still very potent Larrousse LH94, and then later in 2008, at Magny-Cours, the experience went to another level with the more pedigreed Benetton B198 and Williams FW21 which raced in the 1998 and 1999 F1 Championship, respectively. Indeed, 10 years is a long gap but the memory of piloting a Formula 1 car is so vivid that it seems like yesterday. Also, with each stint comes a better state of preparedness. The first time around, I had absolutely no idea what to expect from a 700hp projectile that weighed less than a Nano. And today, I’ve fast-forwarded nearly 20 years to something pretty contemporary.

It’s the Lotus-Renault E20 that Kimi Räikkönen and Romain Grosjean raced in the 2012 Formula 1 season, notching up 303 points along the way, including a win at the Abu Dhabi Grand Prix. It’s nice to know the car I’m driving was actually capable of winning races, but it’s not nice to know that if I actually raced in this car, I would probably have been lapped within the first four laps! This Renault-powered 750hp, 2.4-litre V8 is also the last of an era of high-revving naturally aspirated engines now lost to the current breed of dull-sounding turbo-hybrids.

PREP TALK

What’s not lost is the shattering performance. This is why the Renault crew wasn’t going to let me loose with their fingers crossed just yet – not in something that’s capable of blasting to 100kph in 2.5sec and hitting a top speed of 260kph on one of the two straights at Paul Ricard. A better part of the day went in theory lessons, sitting passenger in a minivan to learn the track, and building up confidence in a Formula 4 car before experiencing the Full Monty.

But first things first, I go through the ritual of donning the race gear that’s essential when you drive any single-seater. I pick XL-sized overalls but choose boots which are one size small. It’s a good way to shrink your feet so you can easily slip them into the tiny pedal box. It’s a hot July day and the three layers of fire-retardant overalls are slowly beginning to feel like a pizza oven. Staying properly hydrated is the key and I’ve lost track of how many bottles of mineral water I gulped down throughout the day.

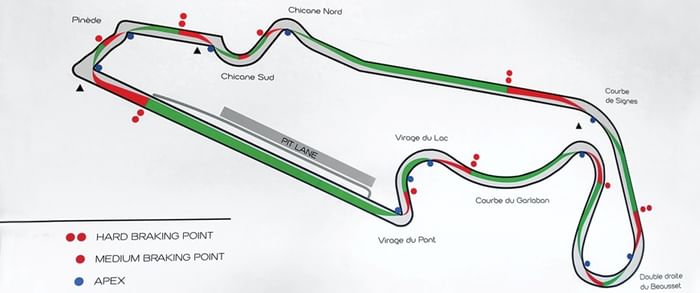

Paul Ricard is a pretty fast circuit but with huge run-off areas, which makes it pretty safe for novice drivers. It’s also the base of the Winfield Racing School which runs the F1 Driving Experience programme for Renault Sport. To keep a better grip on the tightly packed schedule, Winfield used the shorter 3.8km loop of the main 5.8km Grand Prix circuit. It’s not a difficult circuit to learn and a few laps in the minivan alongside one of the instructors and a drivers’ briefing gave me a fair idea of the ideal lines and braking points.

STEPPING UP

The morning session was dedicated to driving the Formula 4 single-seater in 20-minute sessions, interspersed with various interesting activities to test one’s reflexes and hand-eye coordination. Before we jumped into the F4 car we did a few mild exercises to loosen up and were then let loose on the track in groups of three.

The first session was behind a pace car which went gradually faster, and this, for me, was the perfect way to acclimatise to a single-seater after a week of only driving a car that’s nothing like this one – our long-term Tata Hexa. The first few laps were spent memorising the circuit, which looks quite different when you’re sitting just a few inches above it.

The Formula 4 racer had only a 180hp engine but, weighing a scant 400kg, it felt really quick. It had all the sensations of a racing car – terrific grip, brilliant brakes, super-responsive steering and supercar-busting acceleration. The next two sessions were without a pace car and, by now, I could push as hard as I dared. It’s the sheer grip and the braking that is the most astonishing part about a single-seater, and even in this lesser Formula car, the g-forces were so intense that it was hard to hold my neck up through the corners. Pressed against the sides of the cockpit, my arms were so badly bruised that the welts (which I proudly flaunted) took a week to fade.

By the time we got to our third session, my confidence had built up, maybe a bit too much. I put the power down a tad early exiting the second chicane (a tricky, off-camber left-hander) and the F4 snapped into a 180-degree spin. Then came the humiliation when the telemetry from my three sessions was analysed. Compared to the traces of a pro driver, I was embarrassingly off the pace, especially in the faster corners and under hard braking. Well, at least I was better prepared for the different world that was waiting out there.

On an average, it takes an F4 driver another 4-5 years of racing to make it (if at all) into F1. I’m doing the journey in 4-5 hours! Did someone mutter something about a steep learning curve? Well, I feel it’s more of a cliff that I’m about to leap off.

After the F4, the F1 car looks huge, but the cockpit certainly isn’t. You need the agility of an Olympic athlete to even get in and out. Messrs Lewis Hamilton and Sebastien Vettel make it look easy when they leap out of their cars, but believe me, with a 36-inch waist, it really isn’t. It’s hot and claustrophobic in the tight cockpit, which feels like it’s been shrink-wrapped around me. You sit really low, in an almost sleeping position, with your legs raised and knees pressed against the bulkhead. There’s just about enough room for your feet to operate the brake and accelerator; there’s no place for a clutch, and it is now a lever that’s located on the steering wheel. You can only left-foot brake ◊ ∆ and when you do, you need all your weight and then some. I am told I have to stomp the pedal with a pressure of over a 100kg to get the carbon brakes to work effectively.

The steering wheel is uncomfortably close to me so my arms are seriously bent; this makes it hard to turn the steering more than half a lock. I am told that’s all I’ll need on this fast and open circuit which has no really tight bends. I am also instructed not to touch any of the myriad buttons the steering wheel is festooned with, except Neutral which I am asked to press when I come back to the pit lane. To make it even more uncomfortable, the pit crew gives my harness straps one last tug, which takes the wind out

of me.

FAST TENSE

The external starter is shoved into the Renault V8 from behind and it bursts into life. Even at a 6,000rpm idle, the sound of the V8 just inches behind my ears is exhilarating and I can feel my heart beating against the six-point harness. After getting the all-clear signal from the pit crew, I pull the right paddle to engage first gear and slowly release the hand-operated clutch on the steering wheel. This is it. I am driving a Formula 1 car!

I go around the first few corners gingerly, feeling my way around the track in this rocket on wheels, and it’s only when I reach the back straight that I get the confidence to nail the throttle pedal. The acceleration is so violent it feels like I’ve been strapped onto a Brahmos missile, and it’s hard for my brain to process how fast I’m going.

The brutal way this Renault-powered car rockets forward makes it difficult for me to hold my head straight. My helmet is buffeted by the wind, which blurs my vision and the way the tarmac streaks past under me, it looks like it’s been sped up to 4X.

The high-pitched shriek of the engine at 17,000rpm is spine-tingling and there’s no let up in speed in any gear. Third, fourth, fifth, sixth, each gearshift produces a neck-snapping lurch and within a flash, I’m touching 260kph. The car could have gone faster still, beyond 300kph, but Renault has removed the 7th gear to limit speed as a precaution. The Renault motor is ultra-responsive and flies to its dizzy redline so fast that you’re constantly pulling the right paddle on full throttle. My eyes are locked onto the road because everything is happening so fast that it’s hard to even see the shift lights at the top of the steering wheel. I prefer the audible beep you hear through your earplugs (which also double as tiny speakers), to tell you precisely when to shift up.

Straight-line acceleration, ferocious as it is, was the only bit about the F1 car I could exploit and enjoy. Impossible to fathom is the cornering and braking abilities of an F1 car, of which I just about scratched the surface. The power steering is surprisingly light for such a powerful car but make no mistake, it’s sabre-sharp and accurate. It responds best to small and precise inputs and will reward the committed driver. In my case, the truth is that I simply wasn’t going fast enough to get the aero and tyres working. To drive an F1 car properly, you need to have implicit trust in the car because the only way to generate serious downforce is to go even faster. It’s hugely counter-intuitive and my instincts for self-preservation kept getting me to lift my right leg when actually I should have kept it pinned down. Forget the aero, I didn’t even come close to the limits of the hard compound tyres, which I don’t think I got up to operating temperature. But even in my tooling around Paul Ricard, which a Grand Prix driver would at best call a Sunday Drive, the lateral forces were quite immense and it felt like an elephant sitting on the side of my helmet. And then you have the brakes in a Formula 1 car, which don’t work optimally until they get very hot. ‘Optimally’ is a very relative term here, because though the brakes had no feel – with a pedal that felt like you were pressing a concrete brick – they are mind-bogglingly effective. Like most newbies, I end up braking far too early because when your brain is telling you to lift off, you can stay on the throttle for a couple of more seconds. Later, looking at the telemetry, my brake pedal pressure was only 60 percent of what it should have been.

It was all over and back to the pits sooner than I could shout ‘Formula 1’, but those handful of laps felt like the drive lasted a lifetime. The only problem is, every car I drive from now on will seem miserably slow!

The Fastest Taxi Ride

To show me how it’s really done, Stephane Richelmi an LMP2 race driver took me for a taxi ride in a specially adapted two-seater Renault F1 car. The experience was both terrifying and deeply humiliating. Firstly, I’m stuffed into a hole, which is the passenger seat, legs either side of Richelmi, with nothing to really hold on to. There’s no steering wheel obviously, but there’s not even a bar or a strap form to grip firmly tight, Sitting directly behind the driver, I can barely see ahead of me, which is probably a good thing.

From the moment he accelerated out of the pit lane, I wondered if this guy is from a different planet. Approaching the first corner, a tight-hander, I was hard on the brakes, which in my case was Richelmi’s left thigh, while he continued accelerating hard for an extra two seconds. And when he did brake, I thought my eyeballs would hit my visor. My brain just could not process how late you can brake in an F1 car and how devastatingly effective it is at shedding speed.

Through the corners, you can really feel the g-forces and I mean really. When I was driving the Lotus-Renault, I could just about hold my head straight through the corners, but with Richelmi, it was almost impossible. My helmet was bobbing all over the place, buffeted by the wind and intense accelerative forces.

The most white-knuckled bit of the ride was the way Richelmi took Signes, the ultra-fast, right-hand sweeper at the end of the straight, completely flat. There was not even a hint of a lift off, no hesitation, the car wasn’t even on the edge. And to think I hit the brakes each time before Signes! Yes, these guys are from another planet.