Here’s a chilling statistic. On an average, 15 people lose their lives on Indian roads every hour. India, if you didn’t already know, has the worst road safety record in the world. The unfortunate thing is that this loss of life, and accidents in general, are largely, if not entirely, preventable. But to know how to prevent accidents, we need a better understanding of why accidents happen in the first place. And that’s where JP Research comes in. To give you a brief, JP Research is an independent crash investigation organisation involved in first-hand data collection and scientific analysis of accidents. It’s been operating in India since 2006 with an aim to understand the human, vehicle and infrastructure causes of accidents, and the injuries arising thereof. To date, the firm has investigated over 3,000 cases out of its centres at Coimbatore, Pune and Ahmedabad. Studying the mangled metal, the shattered glass and the broken barriers at accident sights is where each case begins. And it’s no easy job.

On-site

We’ve just reached the site of a horrific crash that occurred a few hours ago on the Mumbai-Pune Expressway. All I can see is a heap of twisted metal that’s lying beside a flyover support pillar. The car is so badly deformed, it’s unidentifiable as a Maruti Wagon R. It’s a disturbing sight made worse when I learn the accident claimed all five of the car’s occupants. While I gather my thoughts, the JP Research team is busy unloading their investigation paraphernalia from the back of the support Innova. I’m told, it’s critical to make preliminary observations and make note of volatile evidence such as skid marks, at the earliest. What makes this particular case harder still is that there are no eyewitnesses whose accounts could have served as a starting block. However, police notes help establish the car’s final position of rest before it was moved by the crew of the emergency services in their attempt to rescue the passengers. For the record, JP Research’s team only takes access once the emergency services have left the scene.

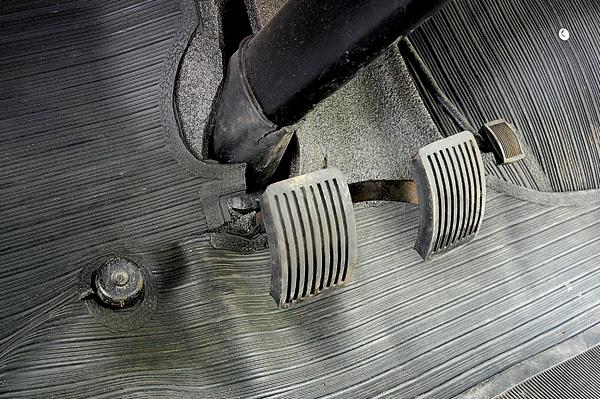

A walk around the car gives the team its first clues as to what could have happened. The way the roof and right-side A, B, C and D-pillars have folded inwards above the belt line suggest the car was tilted on two wheels at the time of impact with the support pillar. This means, it’s possible the driver had lost control of the car. A thorough analysis of the scene substantiates this possibility. Tyre marks help detail the car’s path from the main expressway, onto the shoulder, then the grass-covered run-off area and finally, to the point at which it halted.

The team reckons that a patch of water just before the point at which the car seemingly lost control could be the culprit here. At the moment, aquaplaning seems to be the most probable cause of the accident. I use the term ‘most probable’ here because the team does not want to decisively conclude that it was the cause. Only a full-scale investigation can reveal that. Which is why the team is taking all sorts of photographs and measurements at the scene. The distance from the supposed point of aquaplaning to that of impact is of particular interest. The damaged car’s wheelbase, front track, rear track, length of overhangs, tyre pressures and tread depth are other details that make it to the researcher’s initial deformation sketch. They also measure the intrusion into the passenger cell, and make a note of how the occupants could have moved about in the car to ascertain causes of injury. Meticulousness is a key requirement for the job of data collection. Every little bit of evidence is a crucial piece necessary to solve the larger jigsaw puzzle.